Peacekeeper – Provide Protection

When the rules are broken and the limits on fighting exceeded, the community needs to employ the minimally forceful measures necessary to stop harmful conflict in its tracks. The role of Peacekeeping need not be limited to specialists like the police and UN Peacekeepers, it is a community function that anyone may be called upon to play. When two children fight, adults can step in the middle and, if necessary, physically pull the two apart. The best Peacekeepers never fight. They never fight because they don’t need to. They accomplish their ends by intervening early and using persuasion.

Interpose between parties

Interposing is perhaps the most obvious step a Peacekeeper can take to halt an escalating conflict:

- When two men brawl in a public place, their peers can drag them off each other.

- When rival gangs in Los Angeles started to eye one another, a group of mothers would regularly interpose themselves; after a gang member was killed, they shepherded his “brothers” from the funeral ceremony safely through the enemy gang’s territory.

Neighbors can intervene as well:

- The owner of a small moving company in Lincoln, Nebraska, routinely fields emergency calls from the local Rape-Spouse Abuse Crisis Center. He promptly shows up with his truck and helps the victims of domestic violence escape with their possessions. It can be dangerous work. In one instance, he recalls, “We knew the husband carried guns and might be back soon. We were trying to hurry, but the rain delayed us. Finally, we told her son, ‘Look, if you see your dad returning, you need to call the sheriff.'” Fortunately, they all got out before the husband came back.

Thankfully, there is the sheriff. When a fight breaks out, people can summon the police. “Okay, that’s enough! Let’s break it up!” is a familiar cry.

- To avert violence, police in New York and other cities patrol gang-troubled neighborhoods at night, working together with the community to ensure that teenagers on probation are off the streets.

- In hot spots around the world, interposing is perhaps the chief role for international Peacekeepers, who establish and occupy buffer zones between hostile forces. From Africa to Central America, and from Europe to Asia, men and women from dozens of nations, many of whom are former enemies, work together as Peacekeepers, risking their lives so that others might survive.

Enforce the peace

Sometimes the community needs to go further and use actual force to protect the innocent and stop the aggressor. No matter how strong any single aggressor, the Third Side is potentially stronger.

- Consider how a group of young women freed another young woman being forcibly abducted by six youths in a working-class neighborhood in Mexico. “She was screaming and kicking,” reports anthropologist Laura Cummings. “Then some of these young cholos, four or five girls, came along and were yelling at the fellows to let her go. All but one did. So the girls picked up stones and sticks and started pelting the guy who was dragging the girl. He let go of the girl. . . . The fellows who were with him stood in a circle and did not intervene.” The power of numbers helped liberate the victim while the legitimacy of the young womens’ intervention helped neutralize the attacker’s allies.

Experiments with peace enforcement are occurring on an international scale:

- When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1991 and refused to withdraw his troops, the forces of thirty-eight countries from around the world, operating under a mandate from the United Nations, expelled the Iraqi forces and liberated Kuwait.

- Not only did the world community establish a precedent for repelling aggression against another nation; it also set a bold and remarkable precedent for intervening to defend an endangered minority within a nation. For when Saddam Hussein dispatched his surviving army units to crush the Kurds who had risen up against him, the world community intervened a second time in order to create a protected zone for the Kurds in the north of Iraq.

- While both instances were exceptional and their success was mixed, together they point toward a possible day when genocide and clear aggression will be stopped by the armed will of a united world community.

Preempt violence before it starts

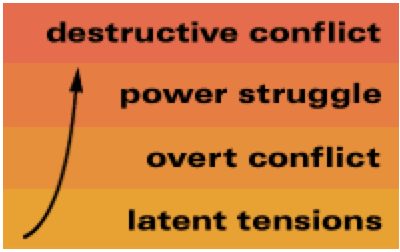

However necessary at the time, a peace enforcement effort such as the Gulf War is always accompanied by tragedy. Much better than stopping an ongoing fight is preempting it before it breaks out. Adequate early warning makes this more than a hypothetical possibility.

- Had international Peacekeepers, for instance, been dispatched to the Kuwait-Iraq border during the week Iraqi troops stood poised for invasion, they might not have been able to physically stop the Iraqi troops from crossing the border, but they would have sent an unmistakable signal to Saddam Hussein of what he could expect if he proceeded with the invasion. Hussein, a ruthless but calculating man, might well have decided to call off his troops.

- An even more dramatic failure to preempt came three years later in Rwanda. As Lieutenant-General Romeo Dallaire, the commander of the local United Nations assistance mission, has attested, and an international panel of senior military leaders has confirmed, an intervention within two weeks of the initial outbreak of violence could have stopped the bloodshed and provided a secure environment in which Hutu and Tutsi leaders might have reduced ethnic tensions. A mere thousand properly trained and armed UN peacekeepers, General Dallaire insists, could have saved the lives of five hundred thousand innocent children, women, and men.

- As a successful example of preempting violence, consider the case of the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia in the six years immediately following its independence. Threatened from the start with annexation by its neighbors, and divided by internal ethnic strife, Macedonia did not collapse thanks in good part to the proactive deployment of an international peacekeeping contingent in 1993. Their presence served to calm tensions and foster a sense of security. While Macedonia’s future remains uncertain as of this writing, the success of the peacekeeping deployment during these years cannot be denied.

The lesson here comes straight out of Sun-Tzu: the best Peacekeepers never fight. They never fight because they don’t need to. They accomplish their ends by intervening early and using persuasion.

- American police forces have learned this lesson, sometimes painfully, over the past two decades. Their old approach when confronted by hostage-takers, for example, was the “John Wayne” method: Surround the place, pull out a bullhorn, give the hostage-taker an ultimatum, “You’ve got three minutes to come out with your hands up!” then lob in the tear gas canisters and charge. The result, more often than not, was dead hostages, dead police, and dead hostage-takers. The 1993 tragedy at Waco, Texas, in which FBI forces stormed the retreat of a religious group, the Branch Davidians, was all too predictable; twenty-one children and seventy-four adults died needlessly in the ensuing fire.

- The alternative and more effective approach is to surround the place, toss in a phone, and talk with the hostage-taker. Talking may take hours, days, or even longer, but with patience, listening, and negotiation skills, the police are able to bring the overwhelming majority of hostage-taking situations to a peaceful end without casualties and with the surrender of the hostage-taker.

Resources

Brief bibliography

- Otunnu, O., M. Doyle, Eds. (1998). Peacemaking and Peacekeeping for the New Century. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Shusta, R., D. Levine, and P. Harris. (1994). Multicultural Law Enforcement: Strategies for Peacekeeping in a Diverse Society. Prentice Hall.

- Ury, William (2000). The Third Side:Why We Fight and How We Can Stop. New York: Penguin.

- Weber, T. and E. Boulding. (1996). Gandhi’s Peace Army : The Shanti Sena and Unarmed Peacekeeping. Syracuse: Syracuse University