Healer – Repair Injured Relationships

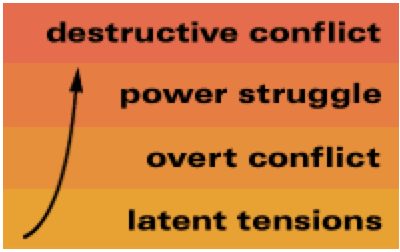

At the core of many conflicts lie emotions – anger, fear, humiliation, hatred, insecurity, and grief. The wounds may run deep. Even if a conflict appears resolved after a process of mediation, adjudication, or voting, the wounds may remain and, with them, the danger that the conflict could recur. A conflict cannot be considered fully resolved until the injured relationships have begun to heal. The role of the Healer is to assist in this process.

Create the right climate

Healing ideally takes place not just at the conclusion of the process of dispute resolution, but at the very start. A psychological wall of suspicion and hostility may separate the parties more definitively than any stone wall. Our task as Healers is to break through this psychological wall.

- “People would call me up angry,” explains Timothy Dayonot, a community relations officer for the University of California at San Francisco. “There’d always be some tough issue – student noise, or traffic, or construction, or radiation from the labs. My approach was to listen to them calmly and then, when they paused for a second, I’d say, ‘Do you have a pen and piece of paper handy?’ ‘Why?’ they’d ask irritably. ‘Because I want you to have my home telephone number. Any time you have a problem, day or night feel free to give me a call.’ They’d be so surprised – they were expecting some kind of bureaucratic runaround – that their tone would change. They’d begin to trust me, and we could then talk through their problem.” In the five years Dayonot held the job, he reported that only once did he receive a call at home – and that was from a complainant who had been so impressed by Dayonot’s open approach that he wanted to offer him a job!

Trust-building can take place not just between individuals but between nations:

- In May 1977, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat shocked the world and offered to fly to Jerusalem, the capital of his enemies, to talk peace. For the first time, he pierced the psychological wall dividing Arabs and Israelis. Up to that point, no Arab leader had publicly acknowledged the existence of the state of Israel, let alone even pronounced its name – it had always been the “Zionist entity.” Overnight, Sadat’s surprise trip to Jerusalem, undertaken within a week of his offer, seized the imagination of millions, both Israelis and Arabs, and created the atmosphere that led to the Camp David peace settlement between Egypt and Israel.

Listen and acknowledge

One of the most powerful methods for healing a relationship is also the simplest. It is to listen, to give one’s complete attention to the aggrieved person for as long as he or she has something to say. Acknowledgement reinforces the effect of listening:

- “You validate their feelings of frustration,” explains a customer service representative who deals daily with angry customers. “You recognize their concerns are legitimate and show that you understand their concerns. Then they calm down.”

- In couples therapy and marriage workshops, husbands and wives learn to listen to and acknowledge each other’s feelings.

Indeed, often what people really want most is a chance to have their grievance heard and acknowledged by others.

Healing comes from acknowledging not just feelings, but also the truth:

- In South Africa after apartheid, President Nelson Mandela established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission with a mandate to collect and investigate the accounts of the victims of apartheid, to offer amnesty for those who confessed their part in atrocities, and to make recommendations on reparations for the victims. The purpose was to use the healing power of the truth to help put the brutal past to rest. Limited by time and resources, the investigation could not possibly satisfy everyone’s need for justice but it did help many victims and their families. After testifying before the commission, one victim, Lucas Baba Sikwepare, who had been cruelly blinded by a police officer known as “Rambo,” declared, “I feel what has been making me sick all the time is the fact that I couldn’t tell my story. But now I – it feels like I got my sight back by coming here and telling you the story.”

Encourage apology

Apologies, sincerely offered, play a vital role in helping emotional wounds heal and restoring injured relationships. As third parties, we often don’t need to do much except offer encouragement.

- “Our last meeting changed how we view our marriage,” announced one husband to the therapist he and his wife had been seeing for some time. “For all that’s been accomplished this past year with you, your question to us about whether we’d ever forgive each other might be the most important thing you’ve ever said.” The therapist was surprised, scarcely remembering having asked the question. Yet it proved to be a turning point. While up to then, the couple had made slow progress backing away from the brink of divorce, after that, the therapist reports, they were a “transformed couple.” “Forgiveness was their goal, and they worked hard on it. Resentments really did wither, hope emerged healthy and vigorous, and they were in love again. Six months after we terminated, they were still going strong.”

The surrounding community’s reaction to violence can often make the difference between vengeance and reconciliation:

- When, in December 1997, the first teenager in more than two years was killed in Boston, the neighbors did not respond the way they had always done before by simply adding another lock and bolt to their doors. Instead, they came in great numbers to offer their condolences to the family and to express their concern about future violence. It was a genuine showing of the Third Side. The slain youth’s friends talked of revenge but at the funeral, the victim’s cousin, Carl Jefferson announced, “His blood is crying out to all of us. What will you do in regards to his life and legacy? Let’s end this violence.” No vengeance killing took place.

Forgiveness is not easy:

- “I’ve heard people say that forgiveness is for wimps,” writes Marietta Jaeger. “Well, I say then that they must never have tried it. Forgiveness is hard work. It demands diligent self-discipline, constant corralling of our basest instincts, custody of the tongue, and a steadfast refusal not to get caught up in the mean-spiritedness of our times. It doesn’t mean we forget, we condone, or we absolve responsibility. It does mean we let go of the hate, that we try to separate the loss and the cost from the recompense or punishment we deem is due. This is what happened to me,” she explains as she recounts how she came to talk with and forgive the sick young man who murdered her seven-year-old daughter.

Resources

- International Reconciliation Coalition

- Victim Offender Reconciliation Program Information and Resource Center

- South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Brief bibliography

- Washington, R. and G. Kehrein. (1996). Breaking Down Walls : A Model for Reconciliation in an Age of Racial Strife. Moody Press.

- Menkin, E.S. and L. Baker. “I Forgave My Sister’s Killer: I couldn’t begin to heal until I let go of my hatred.” Ladies’ Home Journal, December 1995.

- Price, M. “Victim-Offender Mediation: The State of the Art.” VOMA Quarterly Volume 7, Number 3: Fall-Winter 1996.

- Ury, William (2000). The Third Side:Why We Fight and How We Can Stop. New York: Penguin.

- Volkan, V. and Zintl, E. (1993). Life After Loss: Lessons of Grief. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.