The Provider: Prevention Efforts Lead to a Revitalization

Why Once-Violent Neighborhoods Stayed Calm During the Blackout

August 24, 2003

By BRENT STAPLES

New Yorkers who lived through the arson and looting that ravaged the city during the blackout of 1977 were understandably edgy when the lights went out on Aug. 14. But it was clear by late evening that the blackout of 2003 would be nothing like its predecessor. This night did not belong to arsonists or looters; it belonged to families and neighbors who poured into the streets to use the headlights of parked cars for block parties and barbecues.

Why were things so quiet? For one thing, the World Trade Center tragedy taught New Yorkers to recognize the difference between a genuine disaster and a temporary inconvenience. This blackout also favored us by starting during the daylight hours – instead of after dark, like the last one – allowing the Police Department to station officers strategically around the city before nightfall.

A more important difference between this blackout and the last one is the massive, publicly financed reconstruction effort that has rebuilt neighborhoods like the South Bronx from scratch. The program, begun by Mayor Edward Koch in the 80’s, has produced more than 200,000 affordable apartments and houses, revitalizing burned-out communities and turning record numbers of New Yorkers into homeowners with a vested interest in keeping their areas safe.

The recoveries of the South Bronx and Harlem are familiar stories by now. But nowhere was the contrast between the 1977 blackout and the recent one more vivid than in Bushwick, a struggling but improving Brooklyn community that was widely known during the 70’s for its breathtaking lawlessness and decay. Like many poor communities of the period, Bushwick watched its middle class disappear, replaced by the poor families dependent on welfare.

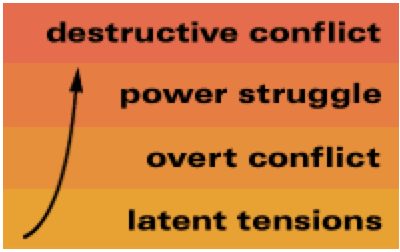

The layoffs and service cuts that came with the city’s fiscal crisis in the 70’s further undermined an already disintegrating community. By the middle of the decade, Bushwick’s decaying wood-frame houses were more valuable to their owners when they were burned for the insurance. Arson became a nightly occurrence. Truck drivers who entered the community first arranged for police escorts. Some department stores refused to deliver to Bushwick at all, requiring buyers to pick up their furniture and appliances at the stores.

This brand of civic quarantine would seem outrageous in New York today. But it was common in the 70’s, when communities like Bushwick, the South Bronx and, to some extent, Harlem were so cut off from the rest of the city that they seemed like distant, third-world countries.

The filmmaker John Sayles lampooned this phobia of minority communities in his 1984 movie “The Brother From Another Planet.” In the film, a subway magician says he can make all the white people disappear from a train heading uptown to black Harlem. At the next stop (the last one before Harlem), the white commuters exit en masse and – poof! – the passengers turn black.

The sense of civic isolation in places like Bushwick was intensified by police officers who took a casual attitude toward crimes in depressed areas that would have been swiftly punished elsewhere. Criminals who learned that they could act with impunity took control of depressed communities. These criminals organized the looting in the 1977 blackout.

In their book about that period – “Blackout Looting!” – Robert Curvin and Bruce Porter found that experienced criminals had actually kept large crowds of less experienced looters at bay until the most valuable merchandise had been stripped from stores and carted away. At the time, the combination of looting and arson proved especially devastating on the 30-block stretch of Broadway in Brooklyn between Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant, where just about every major store was ransacked and many were torched. Bushwick became part of the so-called devastation tour, in which visitors to New York were ferried by bus to view urban blight.

By the early 80’s, New York was faced with a housing shortage and the challenge of rebuilding burned-out, deteriorating neighborhoods. The city committed $5 billion to build affordable housing in these desolate areas with the aim of revitalizing the communities. The rebuilding effort coincided with the rise of community policing, which got officers out of their cars and into closer contact with residents and civic groups. The stabilizing effect has been dramatic in central Harlem – where the home-ownership rate has nearly quadrupled over the last decade alone. The white people who once disappeared so magically from the uptown train now buy houses in Harlem and walk its streets.

A similar transformation is unfolding in Bushwick, where the New York City housing agency has sponsored new construction and the renovation of 4,000 homes and apartments – more than a quarter of them occupied by owners. Earlier this year, more than 2,000 people, including police officers and firefighters, inquired about 61 new houses that are going up in Bushwick, a few of which carry a price tag of more than $300,000. The demand for these houses marks a big change from 20 years ago, when middle-class New Yorkers were even afraid to drive through the neighborhood.

The calm that characterized Bushwick and other rebounding neighborhoods during the recent blackout vindicates the housing initiative begun during the 80’s. The progress of the last 10 years reminds us that investing in the poorest communities benefits the city as a whole.