Gang Warfare: Mothers as Thirdsiders

We are living in the midst of a raging storm of violence.

This storm takes many forms: economic injustice, violence against women, street violence, violence in the home. Violence at work and between differing groups. Violence between nations and against the earth. And that mysterious, undeflected rage we sometimes experience within, aimed simultaneously at the world and at ourselves.

What are we to do, faced with this hurricane of injustice and violation? We can try to pretend this storm does not exist, huddling in our tiny boats and hoping against hope that gale-force winds will not drown us. Or we can take another step. Here is a story of one group of people who confronted this violence by getting out of their little raft of presumed safety and walking on the water.

In the early 1990s in East Los Angeles, a group of women who are members of Dolores Mission Catholic Church, were searching for a solution to the heavy toll that gang violence was taking in their neighborhood. Eight gangs were active in the parish, and gang killings and injuries were an almost daily occurrence. During a particularly violent night, the women were gathered in their prayer group, praying for a solution to this carnage.

That day, the meeting’s scripture reading was about Jesus walking on water. As the mothers prayed, one of their number — electrified with a sudden sense of discovery and consternation — shared with others what she saw as the parallels to their own predicament. The storm on the Sea of Galilee was the gang-warfare in the streets of Boyle Heights. Fearing for their own personal safety, they had retreated behind the locked doors of their homes like the disciples huddled together in their fragile boat. They believed that the only way they would be saved was to get securely out of the line of fire. But, like those in the boat, their paralysis ultimately did not ensure them that they would be secure; they could be killed by misdirected gunfire blasting their homes or they could be shot in broad daylight walking to the market. They were as likely to become victims as much as Jesus’ first century followers were. Both groups could capsize and lose everything in the maddening storm.

“Then,” the woman told the others, “Jesus appears. We, like the disciples, want him magically to solve the crisis. We cry out to him, implore him to save us. But instead, he says to us, “Get out of the boat. Come on: get out of the boat. Leave the illusion of security behind. Get out of the boat and walk on the water. Walk on the water — enter the violence-saturated streets — and we will calm the storm together.”

“What are you saying?” the others asked, a little edgy.

She explained that she felt they were being called to walk together in the midst of the war zone of the gangs.

The others looked at her as if she had suddenly gone mad.

Yet, after a long discussion, that night seventy women (and a few men), began a peregrinacion — a pilgrimage or procession — from one gang turf to the next throughout the barrio . When they encountered startled gang members who were preparing for battle, the mothers invited them to pray with them. They offered them chips, salsa, and soda. A guitar was produced — they were asked to join in singing the ancient songs that had come with them from the Michoacan and Jalisco and Chiapas. Throughout the night, in eight war zones, the conflict was bafflingly, disorientingly interrupted. People were baffled; the gang members were disoriented.

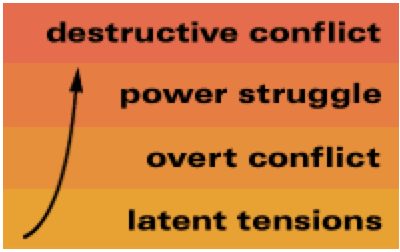

Each night, the mothers walked and within a week there was a dramatic drop in gang-related violence. The members of the newly formed Comite Pro Paz En El Barrio — Committee for Peace in the Neighborhood — had responded to the emergency of the violence being waged in their locality by “breaking the rules of war.” By nonviolently intervening and intruding, they had challenged the old script of escalating violence and retaliation and created, for a time, a new and more creative script. Theirs had been more than a physical journey through their neighborhood. Most significantly, it had been the fundamental spiritual journey from the war zone to the house of love.

By entering this zone of danger, they had created a momentary space for peace. In that space, all the parties were able to glimpse their humanness. The gang-members were able to see, many for the first time, other human beings caring about them. At the same time, the women were able to let go of their paralyzing fear and anger long enough to see the human face of members of the gang. It is no accident that the women christened their night-time journeys “Love Walks.”

But this project did more than briefly interrupt the escalating cycles of violence. By provoking a confrontation with their humanness, they unleashed a process of communication and transformation. Their activity changed the gang-members and themselves. The women listened to the deep anguish of the gang-members about the lack of jobs and about police brutality. This led them, in turn, to develop a tortilla factory, bakery, and child-care center, creating some jobs and giving the gang members an opportunity to acquire job skills. It was also a space where conflict resolution techniques were learned, because people from different gangs worked together in these projects. The women then opened a school. And they shifted from a “Neighborhood Watch” mode — where they were the eyes and ears of the police — to a group trained to monitor and report abusive police behavior, a development that has redefined the relationship between the Los Angeles Police Department and the barrio .

The people in the neighborhood are the first to say that they have not achieved a utopia. There is still poverty, racism, and violence. Nevertheless, they have taken an enormous step toward creating a much more human environment. They did this by risking being human together. Or, in terms of their founding vision, “getting out of the boat” and “walking on water.”