Is War Our Biological Destiny?

New York Times

November 11, 2003

By NATALIE ANGIER

In these days of hidebound militarism and round-robin carnage, when even that beloved ambassador of peace, the Dalai Lama, says it may be necessary to counter terrorism with violence, it’s fair to ask: Is humanity doomed? Are we born for the battlefield – congenitally, hormonally incapable of putting war behind us? Is there no alternative to the bullet-riddled trapdoor, short of mass sedation or a Marshall Plan for our DNA?

Was Plato right that “Only the dead have seen the end of war”?

In the heartening if admittedly provisional opinion of a number of researchers who study warfare, aggression, and the evolutionary roots of conflict, the great philosopher was, for once, whistling in a cave. As they see it, blood lust and the desire to wage war are by no means innate. To the contrary, recent studies in the field of game theory show just how readily human beings establish cooperative networks with one another, and how quickly a cooperative strategy reaches a point of so-called fixation. Researchers argue that one need not be a Pollyanna, or even an aging hippie, to imagine a human future in which war is rare and universally condemned.

They point out that slavery was long an accepted fact of life; if your side lost the battle, tough break, the wife and kids were shipped off as slaves to the victors. Now, when cases of slavery arise in the news, they are considered perverse and unseemly.

The incentive to make war similarly anachronistic is enormous, say the researchers, though they worry that it may take the dropping of another nuclear bomb in the middle of a battlefield before everybody gets the message. “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought,” Albert Einstein said, “but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

Admittedly, war making will be a hard habit to shake. “There have been very few times in the history of civilization when there hasn’t been a war going on somewhere,” said Victor Davis Hanson, a military historian and classicist at California State University in Fresno. He cites a brief period between A.D. 100 and A.D. 200 as perhaps the only time of world peace, the result of the Roman Empire’s having everyone, fleetingly, in its thrall.

Archaeologists and anthropologists have found evidence of militarism in perhaps 95 percent of the cultures they have examined or unearthed. Time and again groups initially lauded as gentle and peace-loving – the Mayas, the !Kung of the Kalahari, Margaret Mead’s Samoans, – eventually were outed as being no less bestial than the rest of us. A few isolated cultures have managed to avoid war for long stretches. The ancient Minoans, for example, who populated Crete and the surrounding Aegean Islands, went 1,500 years battle-free; it didn’t hurt that they had a strong navy to deter would-be conquerors.

Warriors have often been the most esteemed of their group, the most coveted mates. And if they weren’t loved for themselves, their spears were good courtship accessories. This year, geneticists found evidence that Genghis Khan, the 13th century Mongol emperor, fathered so many offspring as he slashed through Asia that 16 million men, or half a percent of the world’s male population, could be his descendants.

Wars are romanticized, subjects of an endless, cross-temporal, transcultural spool of poems, songs, plays, paintings, novels, films. The battlefield is mythologized as the furnace in which character and nobility are forged; and, oh, what a thrill it can be. “The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction,” writes Chris Hedges, a reporter for The New York Times who has covered wars, in “War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.” Even with its destruction and carnage, he adds, war “can give us what we long for in life.”

“It can give us purpose, meaning, a reason for living,” he continues.

Nor are humans the only great apes to indulge in the elixir. Common chimpanzees, which share about 98 percent of their genes with humans, also wage war: gangs of neighboring males meet at the borderline of their territories with the express purpose of exterminating their opponents. So many males are lost to battle that the sex ratio among adult chimpanzees is two females for every male.

And yet there are other drugs on the market, other behaviors to sate the savage beast. Dr. Frans de Waal, a primatologist and professor of psychology at Emory University, points out that a different species of chimpanzee, the bonobo, chooses love over war, using a tantric array of sexual acts to resolve any social problems that arise. Serious bonobo combat is rare, and the male-to-female ratio is, accordingly, 1:1. Bonobos are as closely related to humans as are common chimpanzees, so take your pick of which might offer deeper insight into the primal “roots” of human behavior.

Or how about hamadryas baboons? They’re surly, but not silly. If you throw a peanut in front of a male, Dr. de Waal said, it will pick it up happily and eat it. Throw the same peanut in front of two male baboons, and they’ll ignore it. “They’ll act as if it doesn’t exist,” he said. “It’s not worth a fight between two fully grown males.”

Even the ubiquitousness of warfare in human history doesn’t impress researchers. “When you consider it was only about 13,000 years ago that we discovered agriculture, and that most of what we’re calling human history occurred since then,” said Dr. David Sloan Wilson, a biology and anthropology professor at Binghamton University in New York, “you see what a short amount of time we’ve had to work toward global peace.”

In that brief time span, the size of cooperative groups has grown steadily, and by many measures more pacific. Maybe 100 million people died in the world wars of the 20th century. Yet Dr. Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, has estimated that if the proportion of casualties in the modern era were to equal that seen in many conflicts among preindustrial groups, then perhaps two billion people would have died.

Indeed, national temperaments seem capable of rapid, radical change. The Vikings slaughtered and plundered; their descendants in Sweden haven’t fought a war in nearly 200 years, while the Danes reserve their fighting spirit for negotiating better vacation packages. The tribes of highland New Guinea were famous for small-scale warfare, said Dr. Peter J. Richerson, an expert in cultural evolution at the University of California at Davis. “But when, after World War II, the Australian police patrols went around and told people they couldn’t fight anymore, the New Guineans thought that was wonderful,” Dr. Richerson said. “They were glad to have an excuse.”

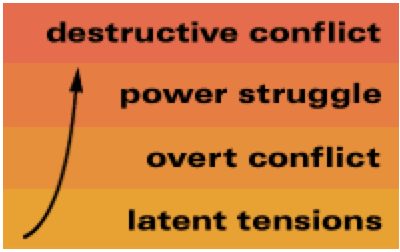

Dr. Wilson cites the results of game theory experiments: participants can adopt a cheating strategy to try to earn more for themselves, but at the risk of everybody’s losing, or a cooperative strategy with all earning a smaller but more reliable reward. In laboratories around the world, researchers have found that participants implement the mutually beneficial strategy, in which cooperators are rewarded and noncooperators are punished. “It shows in a very simple and powerful way that it’s easy to get cooperation to evolve to fixation, for it to be the successful strategy,” he said. There is no such quantifiable evidence or theoretical underpinning in favor of Man the Warrior, he added.

As Dr. de Waal and many others see it, the way to foment peace is to encourage interdependency among nations, as in the European Union. “Imagine if France were to invade Germany now,” he said. “That would upset every aspect of their economic world,” not the least one being France’s reliance on the influx of German tourists. “It’s not as if Europeans all love each other,” Dr. de Waal said. “But you’re not promoting love, you’re promoting economic calculations.”

It’s not just the money. Who can put a price tag on the pleasures to be had from that wholesome, venerable sport – making fun of the tourists?

- s

- Next s