In the community

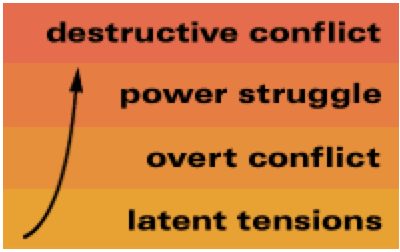

In the early 1990s, teenage violence in Boston seemed out of control. There was a shooting every day and a half, a tripling of the rate over the course of ten years. A nine-year-old boy out trick-or-treating on Halloween was killed by gang crossfire as was a teenager walking to an anti-drug meeting. Yet after more than twenty youngsters died a year from firearms in 1992, the rate fell to zero in 1996. The key, according to Boston Police Commissioner Paul Evans was “collaboration.” The entire community was mobilized. The police worked closely with teachers and parents to search out kids who had missed school or whose grades had dropped. Local government agencies and businesses provided troubled youth with counseling, educational programs, and after-school jobs. Social workers visited their homes. Ministers and pastors mentored them and offered a substitute family for kids who almost never had two and sometimes not even one parent at home. Community counselors, often ex-gang members, hung out with gang members and taught them to handle their conflicts with talk, not guns.

Boston is not alone in making good use of the Third Side. All across America, community disputes of all kinds – from barking dogs to landlord-tenant problems to conflicts over children’s toys left on the sidewalk – are increasingly being mediated by trained community volunteers. “I would recommend the process [of mediated negotiation] to any dispute that looks insoluble,” proclaims Judge Clarence Seeliger after mediation resolved an almost-quarter-century-old bitter dispute in Atlanta over the placement of a highway through local neighborhoods. “They [the third parties] probably kept us from pulling out guns and shooting each other across the table,” says Hal Rives, leader of one of the disputing sides. “I don’t think it [the agreement] would have happened without them.”

The young too are learning to mediate. “If we don’t get mediation, I’d fight her,” says Alisha, a sixth-grader at Martin Luther King School. She had asked a fellow pupil, Elizabeth, a simple question, she said, and Elizabeth had responded by calling her names and “getting in my face ugly.” Instead of fighting, however, Alisha and Elizabeth stomped down to the Center for Conflict Resolution on the ground floor of the school to ask for help from a fellow student trained in mediation. “They resolved the problem by agreeing they would try to get along and not get smart with each other,” explained Patrice Culpepper, the eleventh-grader who mediated the case. “There was follow-up afterward, and they were doing fine.”

In more than five thousand schools across America, children are being trained as peer mediators. They do not wait for problems to come to them; they go into the playgrounds and corridors where the problems are. Typically working in pairs, a boy and a girl, the young mediators approach children who are arguing or fighting and ask them if they want to talk it out. Some simple ground rules are stated: Agree not to interrupt, talk about your feelings, agree to look for a solution. The success rate is high. At Melrose Elementary School in Oakland, for instance, the mediation program was credited with substantially reducing violence and cutting suspensions fiftyfold.

This trend of consensual dispute resolution is not limited to the United States. It is occurring around the world, often building on the traditions of mediation indigenous to each society and culture. The Hawaiians have a tradition of ho’oponopono; the Palestinians call it sulha; and the peoples of the Caucasus use their elders as mediators. Spreading from one society to another, learning from local traditions, mediation is becoming a worldwide movement.