The Aarhus Way of Combating Radicalization in Communities

The series of terrorist incidents that affected France and other parts of Europe in 2015, starting with the Charlie Hebdo massacre led governments, security agencies, and people to take notice of a seemingly strange phenomenon – one of “homegrown terrorists”. The Charlie Hebdo massacre started with two gunmen attacking the office of the French satirical weekly magazine – Charlie Hebdo – for the cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed on the cover of their November 3, 2011 edition of the magazine. The attack spread across three days from January 7, 2015 to January 9, 2015 until the gunmen were captured. It was later discovered that the gunmen were two brothers who were French citizens, born in Paris to Algerian immigrant parents. A superficial scratching of the surface by popular media, in search of the source of such a problem, revealed that the source of these “homegrown terrorists” is radicalization of youth; in particular, Muslim youth. The identification of such a phenomenon allowed the governments to combat this pernicious scourge through multiple avenues. The French[i] and Italian[ii] governments had launched programs to prevent radicalization in their prisons. The French and German governments have taken the job of overhauling the education systems in their respective countries, in order to try to prevent radicalization of youth. For example, in the French education system, the concept of laïcité (secularism) involves an ideology of such a strongly neutral secularism that there is no space for any form of religious expression. The next level of precluding radicalization and ensuring security by the government involves allowing the police broad powers of search and arrest to stem any suspicious activities that foster and propagate terrorism.[iii]

The result of all the above activities is that at this point in Europe, as well as in the United States and in

University students hold placards during a demonstration against satirical French weekly Charlie Hebdo, which featured a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammad as the cover of its first edition since an attack by Islamist gunmen, in Somalia’s capital Mogadishu, January 17, 2015. Source: REUTERS/Feisal Omar

other parts of the world with strong anti-Islamic sentiments, popularly dubbed as Islamophobia, there are large populations of law-abiding and peaceful Muslim citizens who live in fear of their own democratically elected governments. They are constantly on the watch for the possibility of being incarcerated and being deprived of their basic human rights and freedoms. Moreover, it is telling that in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre on January 7, 2015, many French Muslim students in schools refused to participate in the national moment of silence that was organized in solidarity with the French satirical weekly.[iv] In fact, many French Muslim students even sympathized with the attackers and were offended by the weekly’s depiction of Prophet Mohammed.

François Holland’s government got into a moral panic, interpreting the reactions of these French Muslim children as an indication of a failure of the French education system in fostering a unified French identity, as such a rigorously uniform French identity, devoid of any religious and cultural differences and expressions, would allegedly have far-reaching implications for French social harmony and security.[v] There has been little evidence of success for the anti-radicalization campaigns rolled out in the prisons of European countries, though there have been several criticisms about the gaps in that process. For example, there are not enough Muslims chaplains deployed in French prisons with secure job prospects, which supplement their meager earnings.[vi] Moreover, there is a reasonable gripe over the very low numbers of Muslim chaplains employed in these prisons, when more than 50% of the French prison population comprise prisoners of the Islamic faith.[vii] Also, there are arguments that concentrating radical prisoners in one place – the prison – “would reinforce them, while dispersing them would allow them to spread their ideas and find new recruits.”[viii] The lack of trained prison officers could certainly lead to the wrong candidates being identified for isolation in the “secure blocks” created in the French prisons, to stem out radicalization, but that might actually catalyze more radicalization.[ix]

Despite these misdirected and mismanaged steps taken by government authorities to stem the process of radicalization, it is important to note the background and conditions of those who actually get radicalized and travel to Syria, Iraq and other places to fight the holy war.

According to a study by the Soufan Group, most Jihadi foreign fighters are aged between 18 to 29 years, many without a religious upbringing. Furthermore, many are in a vulnerable psychological state of mind, such as being between jobs, experiencing culture shock as university students in a foreign country, and those seeking a sense of belonging.[x] In fact, in a 2015 interview given by Dounia Bouzar, the director of a French NGO established to combat radicalization said that the, “jihadis radicalizing youths hardly talk about Islam at all…Islam is just the final polish.” She added that “the majority of youths radicalized in France have never set foot in a Mosque, and others have never seen Muslims.”[xi] It is also true that the amount of socio-economic discrimination faced by the marginalized Muslim population can lead to further crimes.[xii] For example, in a study conducted by the Institut Montaigne, on religious discrimination in access to employment, it was found that only 10% of Muslims were contacted for job purposes by potential employers as opposed to 16% of Jews and 21% of Catholics. In fact, Muslim men are punished with blatant and obvious discrimination even if their name does not sound “foreign”.[xiii]

In such a contextual setting, Jamal, a young boy of Somalian origin moved with his family to a small town, Aarhus, in Denmark, fleeing the civil war in Somalia. His family was the only black family in a predominantly white neighborhood and being a practicing Muslim did not make life easier for him with the other kids in school. He was often teased for the color of his skin and his religious faith, and asked if he had the same blood as them. Jamal did not fight back as he knew that this would disappoint his father. So, he adopted a different tactic: he studied well, tried to be a good kid and made jokes in class. Soon the other kids and the teachers started to like him and he even started to feel more Danish. Shortly after his family had been on the Hajj, to Mecca and came back, his class teacher organized a debate on Islam. Jamal, infused with a newfound religious identity could not help but retort to a girl who was making statements such as Muslims “terrorize” the West, kill people and stone women. Jamal argued with her and impulsively remarked that “People like you should never exist.”[xiv]

Jamal’s carefully constructed life went off the rails very quickly thereafter. The teacher complained to the principal and the principal told the police. The police questioned Jamal about being a terrorist and he was forced to stay home, missing his school exams. He eventually took his exams, after the police cleared him, but delayed, and hence had to repeat some of his high school. Jamal, a good student all along, was furious about this. Soon after the investigation his mother passed away, leading Jamal to blame the stress of the situation as the cause of her death. Slowly, Jamal started to feel alienated by the West.[xv]

Just then, he began to socialize with a group of young men who had experienced similar instances of discrimination and influenced by the videos of Anwar-al-Awlaki, a famous English-speaking imam, they made plans of traveling to Syria. They shared stories and plans of their travel in the apartment of one of the men. During this time, Jamal got a call from Officer Thorlief Link, from the Danish police department, who had recently been receiving calls from many distraught parents reporting their missing children. With his partner, Allan Aarslev, he discovered that many of these missing children were making trips to Syria to fight the jihad. Officers Link and Aarslev were crime prevention officers within the Danish police department.[xvi]

Alan Aarslev. One of the crime prevention officers in the Aarhus Police Deparment. Source: Scanpix Denmark/USA Scanpix/Sipa

Jamal’s first instinct upon receiving Officer Link’s phone call was to put the phone down. But he was stopped when Officer Link apologized to Jamal about the ordeal that his fellow-officers had put him through and took responsibility for Jamal’s life getting derailed. With this apology, Jamal agreed to meet Officer Link in his office, whereupon he was introduced to his new mentor – Erhan Killic. Killic is a fellow Muslim, a lawyer with a wife and two children, who identifies himself as being completely Danish. Killic too had faced discrimination as a child, but chose a different path for himself. His strong message to Jamal was that he could choose a different path for himself.

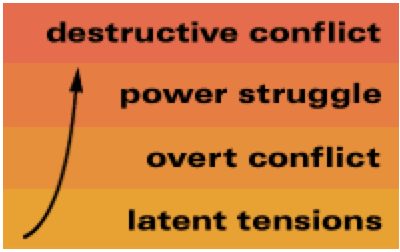

Killic was the first of such mentors to be hired into the Danish police department’s Aarhus Program, which involved such mentors developing constant and positive relationships with mentees such as, Jamal, who were susceptible to the forces of radicalization. According to Arie Kruglanski, a social psychologist, one of the primary motivations for radical behavior in individuals is the quest for personal significance, variously labeled as the need for esteem, achievement, meaning, competence, and control.[xvii]

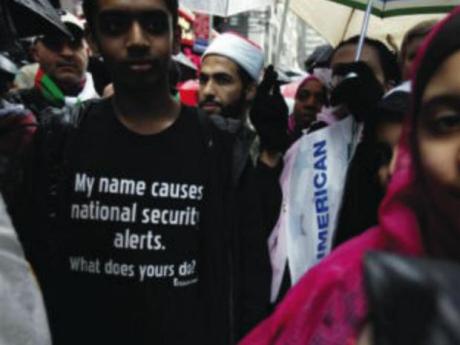

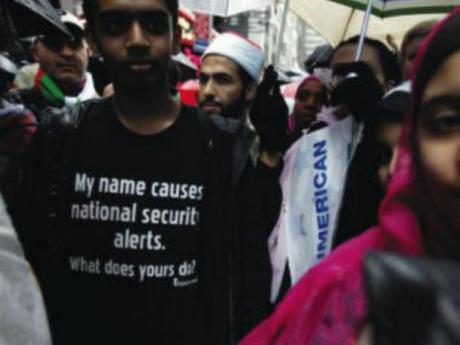

Source: www.barenakedislam.com

In environments with virulent Islamophobia, there is a loss of significance that is experienced by the Muslims and Muslim immigrants, for example, through regular and systematic disrespect of their sacred values, social humiliation through various activities by members of the host group, that lead to lower esteem. These are often exploited by terror propagandists, such as the Al Qaeda and ISIS.[xviii] When the lowering of social and collective esteem reaches extremely low levels, then the individuals who are part of the ostracized sub-groups are willing to even sacrifice their own lives for a greater cause…thereby rendering significance to their selves. Revenge is also a powerful tool for leveling the playing field and by rendering a crushing and humiliating blow to the more powerful host/super-group, one can garner some balance in the situation and avenge their own humiliating experiences. And many times, the act of revenge becomes the greater cause for which the marginalized, ostracized and humiliated sub-group members are willing to give up their own lives.

In these circumstances, it is easy to understand why it is not just Muslim immigrants who are increasingly lured by the seductive call of the ISIS propaganda to fight the jihad, there are reports that a significant portion of the jihadi fighters who form part of the terror units are western fighters, emerging from nations such as France, Germany, Britain, Denmark, Australia.[xix] In fact, there is an over representation of foreign fighters, who tend to be more radical than the average Syrian rebel.[xx] A look at the background of these individuals shows that they have had a history of imprisonment in their respective countries and have generally been socially maladjusted.[xxi] Joining these terrorist organizations provides them with basic psychological needs, such as a sense of belonging, a sense of significance, a sense of respect,[xxii] besides a dash of adventure and some money, which they never had access to in their respective societies of origin.[xxiii]

Some of the crucial steps that the Aarhus Program takes in fighting radicalization are deeply psychological and go to the roots of radicalization, which the regular programs employed by France, Germany, Italy, United States and other countries, do not address. The mainstream programs involve excluding certain sub-groups that exacerbate the situation and fail in the long run.

In Jamal’s story with Officer Link and Killic, several important principles of the Third Side underpin their efforts. In his first phone call to Jamal, Officer Link apologized on behalf of the other members of the Danish police department, who were responsible for Jamal’s life turning into a nightmare. From a Third Side perspective, Officer Link played the role of a Healer. He took responsibility for the actions of his fellow-officers and attempted to repair the negative and distrustful relationship that Jamal had with the Danish police department at large. By introducing Jamal to Killic, and attempting to bring Jamal back into the folds of the mainstream Danish society, Link placed at Jamal’s disposal resources that he otherwise did not have at integrating with the Danish society. Thus, he played the role of a Provider. Killic, played the most crucial role of a Teacher to Jamal – constantly reminding him that he could always choose differently; he could have a well-adjusted and successful life that Killic himself had in Aarhus. Killic shared with Jamal the necessary skills to survive in an environment that may not always be completely accepting of him. Through the example of his own life, Killic showed Jamal that there could be a different possibility to his life.

City of Aarhus, Denmark. Source: Jennifer Joan/Flickr

As of 2012, 34 people traveled from Aarhus to Syria, of which 18 came back. All 18 individuals turned up at Link and Aarslev’s office, as did 330 other potential radicals. However, the Aarhus Program has been most admired for the success rates that it has been exhibiting in the several years since it was implemented. None of the potential radicals have left Aarhus since enrolling in the Program. As of 2015, only one person left for Syria from Aarhus, when traffic from the rest of Europe was mushrooming.[xxiv]

At a time when the world clamps down on what is sometimes a plea for help, the Aarhus Program flipped the script by openly embracing those marginalized and creating a place for them in an otherwise untrusting world.

* * *

[i] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/12/france-battles-to-prevent-islamist-radicalisation-in-jails

[ii] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4091858/Italy-aims-combat-radicalisation-jails-deport-illegal-migrants.html

[iii] http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/07/01/484284791/sweeping-raids-in-france-raise-concerns-about-civil-liberties

[iv] https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/02/why-forced-neutrality-leads-to-polarization/516222/

[v] https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/02/why-forced-neutrality-leads-to-polarization/516222/

[vi] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-islam-radicalisation-idUSKBN0EU1SK20140619

[vii] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-islam-radicalisation-idUSKBN0EU1SK20140619

[viii] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/12/france-battles-to-prevent-islamist-radicalisation-in-jails

[ix] Id.

[x] https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/03/isis-and-the-foreign-fighter-problem/387166/

[xi] https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/02/why-forced-neutrality-leads-to-polarization/516222/

[xii] https://150f11b7-a-62cb3a1a-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/mavalfortwebpage/home/research/Valfort-IM-EtudeAnglaise.pdf?attachauth=ANoY7cpavKroPly6C0Bkdv3lirgxnMakId7n2kOW8OJQqhl5Qb9nr3onFMU9FEc_NFfKgt_gTnDBrnetbrX6pb0A-Vi56MbZigclJ_sc6BxpsMGkc1B7bZMPFrFTtBIMl0RZLcYuEBC7Yzmj8ts7JSYScgf5YyQpF0Cryui7BmFfpjXFWqunK0yki_a5xru3p11oo0RsnPrL8bO4oOvKyvRpeNNSrTTKkFyvBhXPuaklqTfUrFlbpfRIj_8F-Nen_zhD50gE2vI9&attredirects=0

[xiii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/11/23/new-research-shows-that-french-muslims-experience-extraordinary-discrimination-in-the-job-market/?utm_term=.57c439389a5b

[xiv] http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/07/15/485900076/how-a-danish-town-helped-young-muslims-turn-away-from-isis?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=npr&utm_term=nprnews&utm_content=20160715

[xv] Id.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] http://www.gelfand.umd.edu/KruglanskiGelfand(2014).pdf

[xviii] Id.

[xix] https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/03/isis-and-the-foreign-fighter-problem/387166/

[xx] Id.

[xxi] Id.

[xxii] http://www.gelfand.umd.edu/KruglanskiGelfand(2014).pdf

[xxiii] https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/03/isis-and-the-foreign-fighter-problem/387166/

[xxiv] http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/07/15/485900076/how-a-danish-town-helped-young-muslims-turn-away-from-isis?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=npr&utm_term=nprnews&utm_content=20160715