Healing Through Apology: The Case of the Canadian Aboriginal Peoples

TORONTO, ON-MAY 31 – Cathy Stronghearted Woman listens during a drum circle at Queen’s Park in the Walk for Reconciliation in Toronto, May 31, 2015. It was one of several such events across Canada on Sunday leading up to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report on Tuesday. (Marta Iwanek/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

The systematic approach to “civilizing” the aboriginal peoples and integrating them into the mainstream Canadian society has had far-reaching repercussions that has affected the aboriginal peoples across several generations. The Canadian Government of the 19th century believed that uprooting aboriginal children from their home environments, forcing them to learn English and/or French, discouraging them from speaking their native tongue would go a long way in allowing these children to adopt the “Canadian” ways and adapt better to the mainstream culture.[1] With this end goal in mind, a number of residential schools were established in different parts of Canada from 1874 to 1970s, with some schools operating until 1996. This period popularly known as the ‘Residential School Era’, has continued to cast “a long shadow of despair on indigenous communities, and many of the dire social and economic problems faced by aboriginal peoples are linked to that experience.”[2] According to the report of the United Nation’s Special Rappoteur of the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya, “[t]housands of children did not survive the experience and some of them are buried in unidentified graves. Generations of those who survived grew up estranged from their cultures and languages, with debilitating effects on the maintenance of their indigenous identity. That estrangement was heightened during the ‘sixties scoop’, when indigenous children were fostered and adopted into non-aboriginal homes, including outside Canada.”[3]

The stories recounted by the children, who have since grown up are chilling. Edmund Metatawabin, who was the chief of his community in the 1990s, and now 66 years old, recounted that he was five years old when he was sent to the remote church-run school close to his family. One morning, he was ill and threw up the porridge he was eating. He was slapped and told to go upstairs. When he felt better, about four days later, he went back to the dining hall and was forced to eat his own vomit.[4] There were many other stories that covered other forms of psychological, physical and sexual abuse of the children. Besides, minutes from the House of Commons show that it approved the conduct of nutritional experiments on the aboriginal children in the Norway House in northern Manitoba in 1944.[5]

If life in these residential schools was abhorrent, for those children who did manage to survive the abuse, life outside was not much better. The most striking manifestation of the human rights issues faced by the aboriginal peoples, are their distressing socioeconomic conditions in a highly developed country.[6] For example, in 2005, the average Canadian earned Can$ 30,000/- annually, while the median salary for a First Nations person was Can$ 20,000/- and some of the poorest communities among the aboriginal peoples earned on average Can$ 12,000/- annually.[7] The housing situation for the aboriginal peoples is equally bleak, with a startling 45% of the First Nations people living in overcrowded areas, with poor quality of water supply and other infrastructural infirmities that pose a medium to high-level health risk to the inhabitants in these areas. The education that was received by the indigenous children in the residential schools was of very poor quality that did not equip them to continue their higher education – it only served to estrange them from their communities.

Another by-product of the cultural dislocation experienced by the indigenous population that survived the Residential School Era was the lack of inter-generational transmission of child-raising skills and rampant substance abuse, leading to aboriginal children being taken into the care of child services at a rate eight times higher than non-aboriginal children.[8] There is also an over-representation of the indigenous population in the Canadian prison systems. 25% of the Canadian prisons are filled with indigenous populations, while their actual representation in the larger Canadian society is 4%.

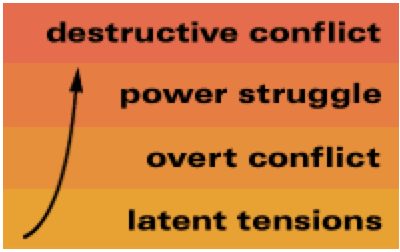

One of the primary roles that the Third Side plays is that of a Healer. The Healer heals injured relationship in the following ways: (1) Creating the right climate for healing relationships and building trust between the aboriginal people and the rest of the Canadian society; (2) Listening and acknowledging the experiences of those who have been victimized during the Residential School Era and beyond; and (3) Encouraging apology from those who were responsible for the atrocities that the aboriginal peoples were subject to.

Understandably, the indigenous population has a distrustful relationship with the Canadian Government. Attempts are being made, to ameliorate this relationship in several ways. For example, the Canadian Government is the first country in the world to recognize and affirm the rights of the aboriginal people by enshrining the recognition, affirmation and protection of the rights of the indigenous population in the Canadian Constitution in 1982. The “Gladue Principle” was developed by the Canadian Courts to consider reasonable alternatives to incarceration while sentencing aboriginal peoples.[9] A Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established on June 1, 2008, with a mandate of five years to investigate and publish a public report on what happened to the children who went to the residential schools.[10]

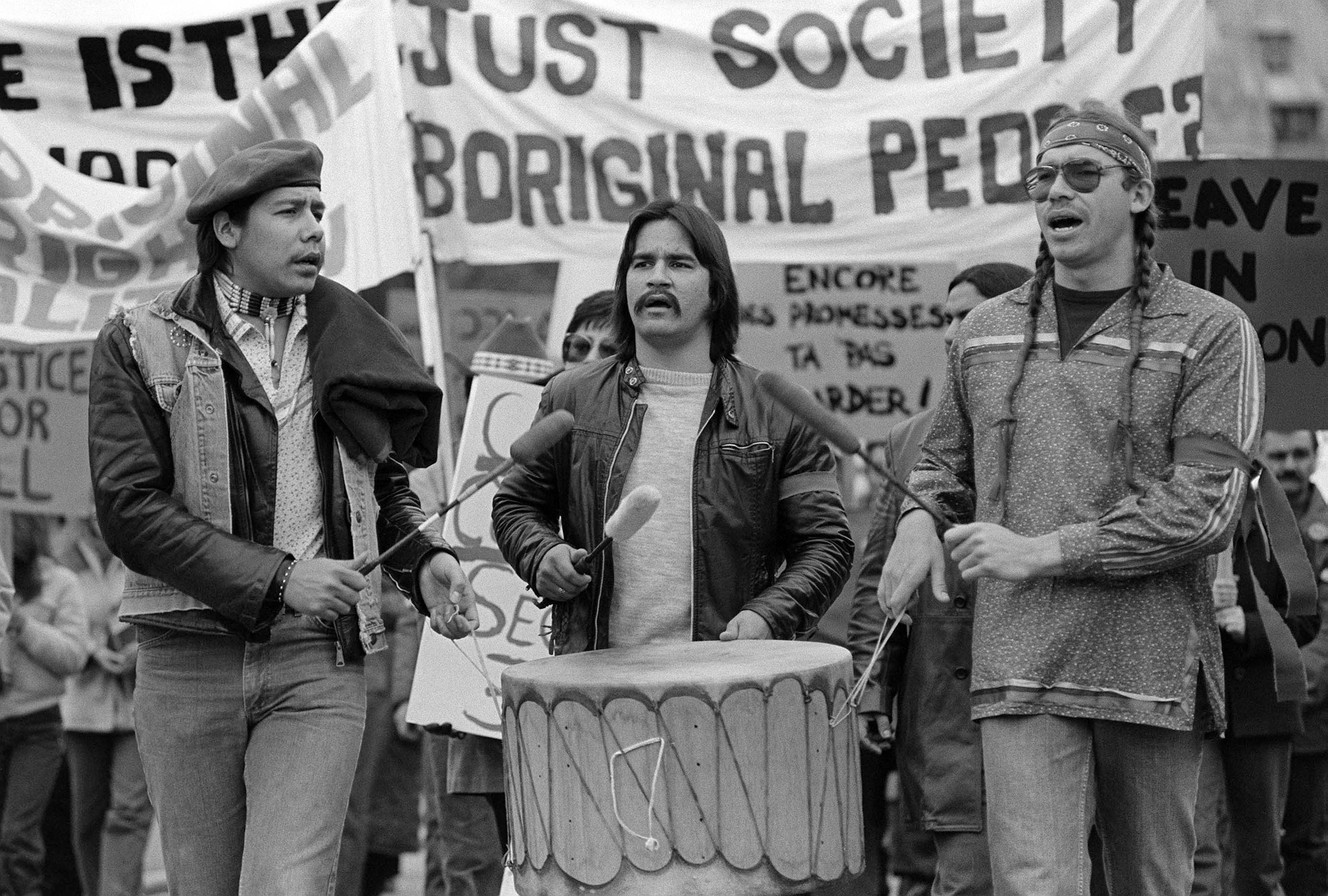

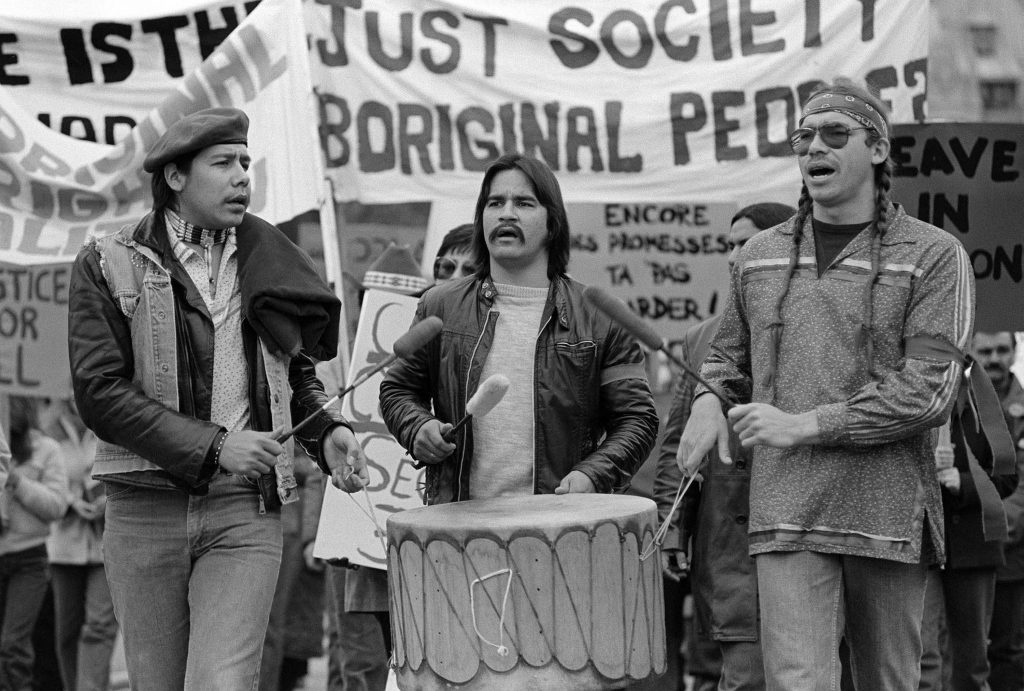

Groups of native people march on Parliament Hill, November 16, 1981, to protest the elimination of aboriginal rights in the proposed constitution. More than one hundred people took part in the march, and a brief ceremony on the Hill. (CP PHOTO/Carl Bigras)

However, a large portion of the hurt and distrust experienced by the indigenous community is psychological in nature. A good portion of their healing process is likely to emerge from the survivors of the residential schools being able to continue to tell their stories and ensure that they are heard and acknowledged.

Residential school survivor Lorna Standingready is comforted by a fellow survivor in the audience during the closing ceremony of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Wednesday, June 3, 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Many churches implicated in the abuse apologized in the 1990s. Archbishop Michael Peers of the Canadian Anglican Church offered an apology on behalf of the church in 1993 stating, “I am sorry, more that I can say. That we were part of a system which took you and your children from home and family.”[11] Four leaders of the Presbyterian Church signed a statement of apology in 1994, which read thus: “It is with deep humility and in great sorrow that we come before God and our aboriginal brothers and sisters with our confession.”[12] On June 11, 2008, the then Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper delivered an official apology to the residential school students in the Canadian Parliament. In recent times, the current Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau invited the Pope to visit Canada to apologize to the aboriginal peoples, in order for Canadians to repair and move forward in their relationship with the indigenous peoples.[13]

Source: https://static.theglobeandmail.ca/4be/video/article27768701.ece/ALTERNATES/w620/Video%3A+Justin+Trudeau+vows+renewal+of+relationship+with+aboriginals

An apology might seem like a trivial gesture in light of the horrors that the indigenous peoples have been subject to, however, the wounds that the aboriginal peoples have run deep and they manifest as anger, fear, humiliation, hatred, insecurity and grief. An apology creates the right climate for the survivors of the residential schools to talk about their experiences. Besides making socio-legal changes that allow to bridge the socioeconomic gap between the aboriginals and the rest of Canada, publicly acknowledging the injustices that they have been subject to would go a long way in creating the right environment for a healing process. To this end, the larger Canadian society, the Catholic Church and the rest of the world can play the role of a Healer in undoing the repercussions of the abusive history of the Canadian aboriginal peoples.

***

[1] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/a-history-of-residential-schools-in-canada-1.702280

[2] http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/docs/countries/2014-report-canada-a-hrc-27-52-add-2-en.pdf

[3] Id.

[4] http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/01/canada-accused-hiding-child-abuse-evidence-201413134751202500.html

[5] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/aboriginal-nutritional-experiments-had-ottawa-s-approval-1.1404390

[6] http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/docs/countries/2014-report-canada-a-hrc-27-52-add-2-en.pdf

[7] http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/05/canada-broken-relationship-wit-2014523123830144334.html

[8] http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/docs/countries/2014-report-canada-a-hrc-27-52-add-2-en.pdf

[9] Id.

[10] http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=39

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/05/trudeau-invites-pope-canada-apology-natives-170529204437411.html